Let me jump to the conclusion: This is an extraordinary book on many levels. It's informative, entertaining often, insightful, sympathetic but not indulgent; it rises to its unusual subject and manages to render its complexity in a straightforward manner that attests to the biographer's talent.

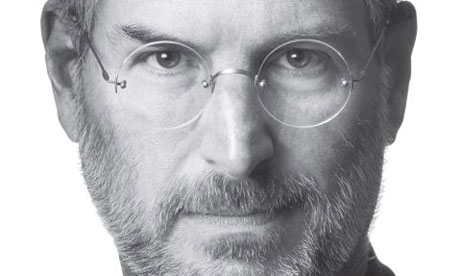

- Steve Jobs: The Exclusive Biography

- by Walter Isaacson

-

- Buy it from the Guardian bookshop

- Tell us what you think: Star-rate and review this book

Last year, Walt Isaacson called to talk about the bio Steve had asked him to write. No surprise there – Dear Leader always wanted the best, and Isaacson had written world-class biographies of Ben Franklin, Einstein and Henry Kissinger.

I told Isaacson how sad this felt, how I perceived Steve's decision as ''putting his affairs in order'' before leaving this Earth. Walt didn't answer directly, but he did say something shocking: Steve had relinquished all control over the book; all decisions were Walt's.

I didn't believe it. I couldn't see Steve giving up control on anything. His fanatical attention to detail is, sorry, was a key ingredient of his success. But Steve's editorial grip on the book went no further than his picture on the cover. In Isaacson's words:

He had never, in two years, asked anything about what I was putting in the book or what conclusions I had drawn. But now he looked at me and said, "I know there will be a lot in your book I won't like." It was more a question than a statement, and when he stared at me for a response, I nodded, smiled and said I was sure that would be true. "That's good," he said. "Then it won't seem like an in-house book. I won't read it for a while, because I don't want to get mad. Maybe I will read it in a year – if I'm still around." By then, his eyes were closed and his energy gone, so I quietly took my leave.To be sure, this isn't your typical CEO encomium where the slightest achievements are remembered as world-changing deeds, and unseemly details are airbrushed into endearing idiosyncrasies.

The arc of Steve's life is the stuff of legends: abandoned at birth; raised in Silicon Valley; an acid-dropping, ashram-dwelling college drop-out, hacker, and co-founder of the most iconic of personal computer companies; fired at age 30; re-inventor of animated movies at Pixar; the struggle to create the NeXT big thing; the return to Apple in the most stunning turnaround the industry had ever seen; reshaping the music industry; building a world-class retail network in his own image; re-inventing the smartphone industry and grabbing half of its profits; and, finally, after 30 years of false starts, making tablets a reality and grabbing iPod-like market and profit share as a result. An arc that saw the unmanageable hippie become the head of one of the world's best-managed companies. And he died just as he reached the pinnacle.

This could tempt both subject and his biographer to produce a statuesque book, a North Korean monument to Dear Leader's achievements. But instead of The Life and Miracles of Saint Steve, we get the gift of truth. We are forced to stare at the reality, or realities of the actual man. Thinking of his children, for whom Steve said the book was, so they got to better know him, this book is a great present. Judging oneself only by comparison to the better side of a parent is a terrible burden. Walt's book gives them an independent look into the incredibly luminous Steve as well as into his sometimes repulsive dark side. Steve's must have hoped to free them from his legend.

On the one hand, Isaacson shows the man who thrilled us with his (almost) unerring taste, with his sense that computers of various sizes and forms were more than merely utilitarian, that they were the objects, the vehicles of an evolving culture. Visionary, artist, leader, innovator … the list of meliorative words goes on, and rightly so: Steve was all these.

On the other hand, Isaacson manages the feat of being, by turns, empathetic, even affectionate and, in the next sentence, unblinkingly factual. The book will confirm everything you've heard about Steve's unpleasant sides, and then some. When learning of his truly pathological eating habits, for example, you'll wonder about his sanity. I don't use the word pathological lightly: you'll see how delusional Steve was when, for eight months, he refused surgery for his diagnosed pancreatic cancer, choosing instead a strict vegan diet, acupuncture and "herbal remedies, and occasionally a few other treatments he found on the internet or by consulting people around the country, including a psychic".

In a similar vein, you'll read what Jony Ive, Apple's senior vice-president of design, Steve's soulmate, had to say about his dark side:

… his way to achieve catharsis is to hurt somebody. And I think he feels he has a liberty and a license to do that. The normal rules of social engagement, he feels, don't apply to him. Because of how very sensitive he is, he knows exactly how to efficiently and effectively hurt someone.Yes, that's also the way Steve was. With everyone, family included.

Knowing or having known many of the characters in the book, I can vouch for its accuracy. But, even more important, I can vouch for its voice. Walt Isaacson got Steve right. He didn't get intimidated, he wasn't seduced into being a groupie, he didn't get nauseated or angry. Instead, he delivered the truest rendition I've read of one of the most complicated people I've known.

His subject's complexity didn't rob Isaacson of his dry wit, such as this observation when observing Jobs after his liver transplant:

As Jobs got better, much of his feisty personality returned. He still had his bile ducts.Or from recording memorable Bill Gates quotes such a this one:

I've been predicting a tablet with a stylus for many years," he told me. "I will eventually turn out to be right or be dead.(Not so fast, Bill, we love to have you and Ballmer around.)

In my view, the only way to keep one's sanity when dealing with Steve was to stay ambivalent, to force oneself to harbour contradictory feelings about him. Easier said than done. In my case, over time, feelings of admiration and affection have taken over when watching the feats and the struggle. Reading Walt's book was a helpful and, at times, painful reminder of who Jobs actually was.

JLG@mondaynote.com

source

No comments:

Post a Comment